Farewell - Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), A Symphony for Tenor and Contralto (or Baritone) and Orchestra, after Hans Bethge’s The Chinese Flute

A Timeline of Mahler's Music

Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), A Symphony for Tenor and Contralto (or Baritone) and Orchestra, after Hans Bethge’s The Chinese Flute

1878-1880

-

I. The Drinking Song of the Earth’s Sorrow” (Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde)

-

II. “The Lonely Man in Autumn” (Der Einsame im Herbst)

-

III. “Of Youth” (Von der Jugend)

-

IV. “Of Beauty” (Von der Schönheit)

-

V. “The Drunkard in Spring” (Der Trunkene im Frühling)

-

VI. “The Farewell” (Der Abschied)

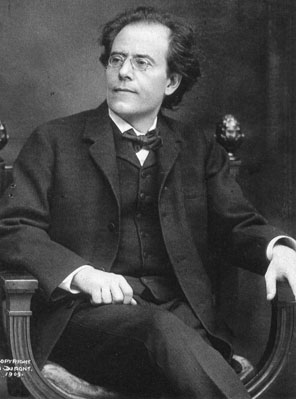

Gustav Mahler made the first sketches for this music in 1907 but did most of the work in the summer of 1908, completing the last song in short score—that is, with the instrumentation indicated but not fully written out—on September 1 that year. The full score was finished in 1909. Mahler did not live to hear this work, whose first performance was given by his friend, disciple, and former assistant, Bruno Walter, in Munich on November 20, 1911. Walter chose two American singers from the roster of the Vienna Court Opera, William Miller and Mme. Charles Cahier (Sara Jane Layton Walker from Nashville, Tennessee, who always used her married name).

The score calls for three flutes and piccolo, three oboes (third doubling English horn), three clarinets with high clarinet in E‑flat and bass clarinet, three bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon), four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, bass tuba, two harps, mandolin, celesta, timpani, glockenspiel, tam-tam, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, tambourine, snare drum, and strings.

These notes are used by kind permission of the estate of Michael Steinberg and are taken from the complete notes in his Oxford volume “The Symphony”.

Early in 1907, Gustav Mahler was given a newly published verse collection of German translations from the Chinese, Hans Bethge’s Die chinesische Flöte, The Chinese Flute. Mahler, distracted and overworked, put the book aside. Late that summer, when he came across the gift again, he was worse than overworked. In July, his daughter Maria, four‑and‑a‑half, had died of scarlet fever and diphtheria, and he had learned that he himself suffered from a severe heart condition. Work pulled him out of despondency. Those melancholy verses spoke to Mahler with singular urgency. He began sketches, and the songs were his chief project for the following summer.

It was clear to him from the beginning that he was writing no ordinary song cycle but something larger and more cohesive, something, in fact, symphonic. Bruno Walter recalled Mahler’s describing the work as “a symphony in songs,” and Mahler did in the end head the score “a symphony for tenor and contralto (or baritone) and orchestra.” Ever since Bruno Walter chose a contralto when he conducted the first performance in 1911, most performances have followed Walter’s lead. But Mahler expressed no clear preference, and in fact when the poems’ speakers are referred to, the references are masculine.

Das Lied von der Erde is not, however, among Mahler’s numbered symphonies. It would be his ninth, but, with Beethoven and Bruckner in mind, he was superstitious about ninth symphonies and convinced that he would not be granted the time to go beyond that freighted number. He thought to put one over on the gods by not assigning a number to the symphony after the Eighth, and when he finished the symphony he called No. 9 he triumphantly told Alma that it was of course “really the Tenth” and that the danger was past. But the gods were not taken in by Mahler’s bookkeeping, and death claimed him as he was at work on the symphony he called No. 10.

“Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde” (“The Drinking Song of the Earth’s Sorrow”)—The poet is Li T’ai‑po, born in Szechwan in 701. Legend has him drown when he fell out of a boat by moonlight, drunk, whereupon a dolphin bore him to sea and immortality; in duller fact, he died in bed in the year 762. Wine was, however, one of his favored topics. Here he invites us first to contemplate the brevity of human life and then to drain our goblets. From Li’s melancholy poem Mahler makes a savage song. It explodes with the fierce call of all four horns in unison and with the cackle of sardonic laughter in woodwinds, trumpets, and violas. It is a song full of bittersweet sounds and of ugly ones. As musical composition it is as extraordinary as it is a penetrating setting of a poem. Mahler spreads a feast of variation: Nothing appears twice the same way, and even the refrain of “Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod” is sung each time at a higher pitch than before. Along with this developing variation (to borrow Schoenberg’s phrase about Brahms), we find Mahler extending the resources of counterpoint by means of what we might call simultaneous variation. At (for example) the passage about the span of human life—“Nicht hundert Jahre darfst du dich ergötzen”—tenor and violins have almost the same melody, but the fascination is in the almost-but‑not‑quite, in the way what seems to be a single line keeps splitting in two. This sort of multiple vision recurs throughout this song (and others in Das Lied von der Erde, particularly the last). As Mahler grew older, his poignant and vivid art was tied more and more to his bold polyphonic fantasy. In this song we meet his craft in its most prodigiously developed state, and in the service of communicative powers that border on the annihilating. “What do you think,” he asked Bruno Walter, “Is it at all bearable? After hearing this, won’t people want to do away with themselves?”

After this ferocious tavern homily comes the contrast of the second song’s fatigued quiet. The poet of “Der Einsame im Herbst” (“The Lonely Man in Autumn”) is Chang Tsi. Muted violins paint the background against which the oboe projects its plaintive song, a song more elaborate than is for many minutes granted the baritone. His declamation is a series of restrained scale passages. Only with the thought of the beloved place of rest does passion begin to inform the singing. The anguished plea to the sun of love—“will you never shine again?”—is a sudden flight of ardent song, but before the sentence is finished Mahler reverts to the bleak opening music.

There follows, after these intensely serious songs, a triple intermezzo, all on poems by Li T’ai‑po. First “Von der Jugend” (“Of Youth”)—the orchestra even pretends for a moment to be Chinese in this dexterously charming projection of a genre scene so familiar as to be a cliché. Under the bits of pentatonic melody and the ding of the triangle it is all quite Viennese. And in a moment it is over.

“Von der Schönheit” (“Of Beauty”) is more spacious, and while “Of Youth” is the delighted observation of a single mood, we now have a song as varied as the pounding heartbeats of the seductive girls with their great yearning eyes. The song rises to a fiery gallop, only to return to languor. The music continues the delicious erotic reverie long after words have failed.

“Der Trunkene im Frühling” (“The Drunkard in Spring”) is perhaps our friend from the first song, but in reckless good humor. The realization that spring is come softens him—the violin solo is the quintessential Mahler pastoral tune—but he retreats, from his own tenderness to the safety of his wine flask while the music returns to the bright, bass‑starved sound of its opening page.

“Der Abschied” (“The Farewell”) constitutes almost half the work. Here Mahler made a conflation of two poems. The first is by Mong Kao‑Jen; the second, beginning with “Er stieg vom Pferd,” is the work of Wang Wei. These eighth-century poets were themselves friends who addressed these respective verses to one another.

The song begins with a deep tolling over which the oboe keens. Veiled violins bring consolation, but the music disintegrates. In less than a minute-and-a-half, Mahler has given us the basic material for the movement. The silence that follows the disintegration prepares the entrance of the voice. At this moment, the music in effect begins over—or, if you prefer, what we hear now is a variation on the first eighteen measures, a variation in which the tolling is reduced to a sustained low C on the cellos, the oboe’s part is taken by the flute, and the voice assumes the contours of the horns’ and clarinets’ sighs. After the flute dies away, the music makes a third start of tolling and lament; before the double song is done, there will have been nine such new beginnings. They are widely various in tone and mood, in key, in scale, in their propensity to introduce new material or avoid it. Developing variation is here the governing principle. The idea of simultaneous variation is also very much with us. Perhaps the richest instance of it occurs in one of the most lovely phrases in Das Lied von der Erde, the one about the rising moon: “O sieh! Wie eine Silberbarke schwebt/Der Mond am blauen Himmelssee herauf,” where baritone, clarinets, and cellos have almost the same melody, almost at the same time.

The first two stanzas and the beginning of the third are scene‑setting. With “Ich sehne mich, O Freund” comes a sudden surge of feeling. Here, with the fresh sound of mandolin, Mahler gives us a new melody of miraculous breadth. A broad orchestral interlude marks the break between the two poems and is also the most magnificent of Mahler’s funeral marches. The music for the second poem is a condensed re‑experiencing of that for the first. The great hymn to spring—“Die liebe Erde”—brings the earlier “new melody” back in still more beautiful form. Voice and instruments reiterate “ewig” (“forever”) until sound and silence become one. Mahler sings a farewell, but his song of and to the earth is, at its close, a song of love and of life.

— Michael Steinberg

German

Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde

Schon winkt der Wein im goldnen Pokale,

Doch trinkt noch nicht, erst sing ich euch ein Lied!

Das Lied vom Kummer soll auflachend

In die Seele euch klingen.

Wenn der Kummer naht, liegen wüst die Gärten der Seele,

Welkt hin und stirbt die Freude, der Gesang.

Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod.

Herr dieses Hauses!

Dein Keller birgt die Fülle des goldenen Weins!

Hier diese Laute nenn ich mein!

Die Laute schlagen und die Gläser leeren,

Das sind die Dinge, die zusammen passen.

Ein voller Becher Weins zur rechten Zeit

Ist mehr wert als alle Reiche dieser Erde!

Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod.

Das Firmament blaut ewig und die Erde

Wird lange fest stehn und aufblühn im Lenz.

Du aber, Mensch, wie lang lebst denn du?

Nicht hundert Jahre darfst du dich ergötzen

An all dem morschen Tande dieser Erde!

Seht dort hinab! Im Mondschein auf den Gräbern

Hockt eine wild‑gespenstische Gestalt—

Ein Aff ist’s! Hört ihr, wie sein Heulen

Hinausgellt in den süssen Duft des Lebens!

Jetzt nehmt den Wein! Jetzt ist es Zeit, Genossen!

Leert eure goldnen Becher zu Grund!

Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod!

--Li T’ai-po

Der Einsame im Herbst

Herbstnebel wallen bläulich überm See;

Vom Reif bezogen stehen alle Gräser;

Man meint’, ein Künstler habe Staub von Jade

Über die feinen Blüten ausgestreut.

Der süsse Duft der Blumen ist verflogen;

Ein kalter Wind beugt ihre Stengel nieder.

Bald werden die verwelkten, gold’nen Blätter

Der Lotosblüten auf dem Wasser ziehn.

Mein Herz ist müde. Meine kleine Lampe

Erlosch mit Knistern;

Es gemahnt mich an den Schlaf.

Ich komme zu dir, traute Ruhestätte!

Ja, gib mir Ruh, ich hab Erquickung not!

Ich weine viel in meinen Einsamkeiten.

Der Herbst in meinem Herzen währt zu lange.

Sonne der Liebe, willst du nie mehr scheinen,

Um meine bittern Tränen mild aufzutrocknen?

--Chang Tsi

Von der Jugend

Mitten in dem kleinen Teiche

Steht ein Pavilion aus grünem

Und aus weissem Porzellan.

Wie der Rücken eines Tigers

Wölbt die Brücke sich aus Jade

Zu dem Pavilion hinüber.

In dem Häuschen sitzen Freunde,

Schön gekleidet, trinken, plaudern,

Manche schreiben Verse nieder.

Ihre seidnen Ärmel gleiten

Rückwarts, ihre seidnen Mützen

Hocken lustig tief im Nacken.

Auf des kleinen Teiches stiller

Wasserfläche zeigt sich alles

Wunderlich im Spiegelbilde.

Alles auf dem Kopfe stehend

In dem Pavillon aus grünem

Und aus weissem Porzellan;

Wie ein Halbmond steht die Brücke,

Umgekehrt der Bogen. Freunde,

Schön gekleidet, trinken, plaudern.

--Li T’ai-po

Von der Schönheit

Junge Mädchen pflücken Blumen,

Pflücken Lotosblumen an dem Uferrande.

Zwischen Büschen und Blättern sitzen sie,

Sammeln Blüten in den Schoss und rufen

Sich einander Neckereien zu.

Goldne Sonne webt um die Gestalten

Spiegelt sie im blanken Wasser wider,

Sonne spiegelt ihre schlanken Glieder,

Ihre süssen Augen wider.

Und der Zephir hebt mit Schmeichelkosen das Gewebe

Ihrer Ärmel auf, führt den Zauber

Ihrer Wohlgerüche durch die Luft.

O sieh, was tummeln sich für schöne Knaben

Dort an dem Uferrand auf mut’gen Rossen?

Weithin glänzend wie die Sonnenstrahlen,

Schon zwischen dem Geäst der grünen Weiden

Trabt das jungfrische Volk einher!

Das Ross des einen wiehert fröhlich auf

Und scheut und saust dahin,

Über Blumen, Gräser, wanken hin die Hufe,

Sie zerstampfen jäh im Sturm die hingesunknen Blüten,

Hei! Wie flattern im Taumel seine Mähnen,

Dampfen heiss die Nüstern!

Goldne Sonne webt um die Gestalten,

Spiegelt sie im blanken Wasser wider.

Und die schönste von den Jungfraun sendet

Lange Blicke ihm der Sehnsucht nach.

Ihre stolze Haltung ist nur Verstellung.

In dem Funkeln ihrer grossen Augen,

In dem Dunkel ihres heissen Blicks

Schwingt klagend noch die Erregung ihres Herzens nach.

--Li T’ai-po

Der Trunkene im Frühling

Wenn nur ein Traum das Leben ist,

Warum dann Müh und Plag?

Ich trinke, bis ich nicht mehr kann,

Den ganzen, lieben Tag!

Und wenn ich nicht mehr trinken kann,

Weil Kehl und Seele voll,

So tauml’ ich bis zu meiner Tür

Und schlafe wundervoll!

Was hör ich beim Erwachen? Horch!

Ein Vogel singt im Baum.

Ich frag ihn, ob schon Frühling sei.

Mir ist als wie im Traum.

Der Vogel zwitschert:

Ja! Der Lenz ist da,

Sei kommen über Nacht!

Aus tiefstem Schauen lausch ich auf,

Der Vogel singt und lacht!

Ich fülle mir den Becher neu

Und leer ihn his zum Grund,

Und singe, bis der Mond erglänzt

Am schwarzen Firmament!

Und wenn ich nicht mehr singen kann,

So schlaf ich wieder ein.

Was geht mich denn der Frühling an?

Lasst mich betrunken sein!

--Li T’ai-po

Der Abschied

Die Sonne scheidet hinter dem Gebirge.

In alle Täler steigt der Abend nieder

Mit seinen Schatten, die voll Kühlung sind.

O sieh! Wie eine Silberbarke schwebt

Der Mond am blauen Himmelssee herauf.

Ich spüre eines feinen Windes Wehn

Hinter den dunklen Fichten!

Der Bach singt voller Wohllaut durch das Dunkel.

Die Blumen blassen im Dämmerschein.

Die Erde atmet voll von Ruh und Schlaf.

Alle Sehnsucht will nun träumen,

Die müden Menschen gehn heimwärts,

Um im Schlaf vergessnes Glück

Und Jugend neu zu lernen!

Die Vögel hocken still in ihren Zweigen.

Die Welt schlaft ein!

Es wehet kühl im Schatten meiner Fichten.

Ich stehe hier und harre meines Freundes;

Ich harre sein zum letzten Lebewohl.

Ich sehne mich, O Freund, an deiner Seite

Die Schönheit dieses Abends zu geniessen.

Wo bleibst du? Du lässt mich lang allein!

Ich wandle auf und nieder mit meiner Laute

Auf Wegen, die von weichem Grase schwellen.

O Schönheit! O ewigen Liebens- Lebenstrunk’ne Welt!

--Mong Kao-Jen

Orchestrales Zwischenspiel

Er stieg vom Pferd und reichte ihm den Trunk

Des Abschieds dar. Er fragte ihn, wohin

Er führe und auch warum, es müsste sein.

Er sprach, und seine Stimme war umflort:

“Du mein Freund,

Mir war auf dieser Welt das Glück nicht hold!

Wohin ich geh? Ich geh, ich wandre in die Berge.

Ich suche Ruhe für mein einsam Herz.

Ich wandle nach der Heimat, meiner Stätte.

Ich werde niemals in die Ferne schweifen.

Still ist mein Herz und harret seiner Stunde!

Die liebe Erde allüberall

Blüht auf im Lenz und grünt

Auf’s neu! Allüberall und ewig

Blauen licht die Fernen!

Ewig . . .ewig . . .”

--Wang Wei

German translations by Hans Bethge, from the Chinese.

English

The Drinking Song of the Earth’s Sorrow

The wine is sparkling in the golden goblet,

but don’t drink yet. First I’ll sing you a song!

The song of sorrow will

echo through your souls, laughing out loud.

When sorrow nears, the soul’s gardens wither;

joy and song die.

Life is dark, as is death.

Master of this house!

Your cellar holds a wealth of golden wine!

I call this lute my own!

To strike the lute and empty the glasses—

these things go together.

A full goblet at the right time

is worth more than all the kingdoms of earth!

Life is dark, as is death.

The sky is blue forever, and the earth

will endure, and bloom in spring.

But you: How long will you live?

You are not allowed to enjoy

the rotten trifles of this earth for even a hundred years.

Look down there! In the moonlight, on the graves

squats a wild and ghostly figure.

It’s an ape! Listen as his cries

pierce the sweet air of life!

Now take the wine! Now it’s time, friends!

Drain your golden cups!

Life is dark, as is death!

--Li T’ai-po

The Lonely Man in Autumn

Blue mists of autumn float over the lake;

the grasses are covered with hoar-frost.

You might think an artist had sprinkled jade dust

over the delicate buds.

The sweet scent of the flowers has vanished;

a cold wind bends their stems.

Soon the wilted, golden lotus petals

will float across the water.

My heart is weary. My little lamp

crackled and died;

it speaks to me of sleep.

I am coming to you, dear resting place!

Yes, give me rest. I need to be refreshed.

I often weep in my solitude.

The autumn in my heart is lasting too long.

Sun of love, will you never shine again

and softly dry my bitter tears?

--Chang Tsi

Of Youth

In the middle of the pond

stands a pavilion of green

and white porcelain.

The jade bridge

arches like a tiger’s back

across to the pavilion.

Friends are gathered in the little house,

dressed beautifully, drinking, talking,

some writing verses.

Their silken sleeves glide

backward, their silken caps

perch on the backs of their necks.

On the pond’s motionless

surface, everything

is oddly mirrored.

Everything stands on its head

from inside the pavilion of green

and white porcelain.

The bridge stands like a half‑moon,

its arch reversed. Friends,

dressed beautifully, are drinking, talking.

--Li T’ai-po

Of Beauty

Young girls are picking flowers,

picking lotus flowers at the water’s edge.

They sit among bushes and leaves,

gathering flowers in their laps and

bantering with each other.

Golden sun bathes these images,

mirrors them in bright water.

The sunlight, reflected from their slender limbs,

is mirrored in their sweet eyes.

And the caressing breeze lifts their

sleeves, carries the magic

of their perfumed scent through the air.

Look: What handsome boys come galloping

along the shore on proud horses?

Gleaming like the sun’s rays,

the young men come riding

between the trees and green meadows.

One rider’s horse neighs happily

and runs to and fro,

hooves flying across flowers and grass.

In a storm they trample the fallen buds.

How the mane flows,

and how the nostrils steam!

Golden sun bathes these images,

mirrors them in bright water.

And the loveliest of the maidens

sends the rider long looks of yearning.

Her proud bearing is only show.

In the gleam of her large eyes,

in the darkness of her warm gaze,

her heart, sad and excited, follows him.

--Li T’ai-po

The Drunkard in Spring

If life is just a dream,

why are we tormented with troubles?

I drink until I can drink no more,

the whole blessed day!

And when I can drink no more

because throat and soul are full,

I’ll stagger to my door

and sleep wonderfully!

What do I hear as I awake? Listen!

A bird is singing in the tree.

I ask him if spring is already here.

It’s as if I’m in a dream.

The bird chirps:

“Yes! Spring is here.

It arrived during the night!”

Pondering deeply, I listen.

The bird sings and laughs.

I fill my cup again

and empty it to the last drop,

and I sing until the moon gleams

in the black firmament!

And when I can sing no more,

I go to sleep again.

What does spring matter to me?

Let me be drunk!

--Li T’ai-po

The Farewell

The sun departs behind the mountains.

The cool shadows of evening

descend into all the valleys.

Look! Like a ship of silver

the moon floats in heaven’s blue lake.

I feel a light wind stir

behind the dark firs.

The brook sings so beautifully in the darkness.

The flowers grow pale in the twilight.

The earth breathes deeply, filled with peace and sleep.

Now yearning inclines toward dreams,

the weary turn homeward

to sleep, where they recapture

forgotten happiness and youth.

The birds crouch quietly on their branches.

The world falls asleep!

From the shadows of my firs comes a cool rustling.

I stand here and await my friend;

I await his last farewell.

Oh, my friend, I long to enjoy

this evening’s beauty at your side.

Where are you? You are leaving me alone so long!

I wander back and forth with my lute

along paths covered with soft grass.

Oh beauty! Oh world, drunk with love and life forever!

--Mong Kao-Jen

Orchestral Interlude

He dismounted and offered him the drink

of farewell. He asked him where

he was heading, and also why he had to go.

He spoke, and his voice was soft with tears:

“My friend,

fortune was not kind to me in this world.

Where am I going? I go to travel in the mountains.

I seek peace for my lonely heart.

I’ll turn toward home, where I belong.

I will never stray far.

My heart is calm and awaits its hour.

Everywhere, the beloved earth

blooms in the spring and

is newly green! Everywhere and forever

the distances are blue and bright!

Forever . . . forever . . . ”

--Wang Wei

Translations: Larry Rothe