-

“ I am three times homeless...”

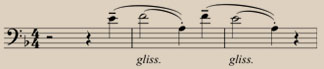

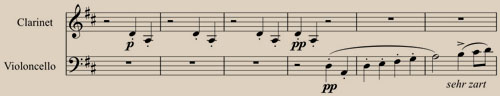

Many commentators have detected “something Jewish” about Mahler’s lyrical utterances, for instance, his frequent use of sighing motifs in his melodies. Certainly, this gesture is a natural expression of melancholy and is liberally used in music of gypsies, Jews, and people from the outlying areas of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Here, at a moment of grave stillness in the development of the first movement of the first symphony, the cellos “sigh.”

Isolation

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

Mahler pushes his orchestra to emulate the expressivity of the human voice. He marks his parts with very detailed dynamics, bowings, articulations, and other instructions. Here, he gets the cellos to sigh by playing glissando, sliding from one note to the next. In the First Symphony, the rest of the orchestra stand still while the cellos ask a searching question, using the alternation of major and minor harmonies to convey the expressive meaning.

Counterpoint

-

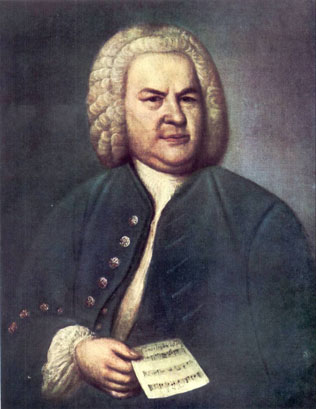

Mahler’s academic musical education with Bruckner at the Vienna Conservatory steeped him in the German romantic tradition, including the great baroque masters. He later said: “In Bach, all the seeds of music are found, as the world is contained in God. It‘s the greatest polyphony that ever existed!” Listen to the competing musical lines in Bach’s fourth Brandenburg Concerto and compare the effect to that of Mahler's symphonic counterpoint.

The Cost of War

Mahler's Methods

-

The funeral march from Donizetti’s opera Dom Sebastien was as famous in the nineteenth century as Chopin’s Funeral March, and was certainly familiar to Mahler from military ceremonies in Iglau. The young Mahler also performed Liszt’s transcription for piano of this same march at a childhood recital.

-

It must have haunted him down the years, because he quoted the march’s major-minor harmonies in the last of his Songs of a Wayfarer (Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen). The narrator sings of loneliness and isolation to the cadences of a funeral march: “I went out into the quiet night, over the dark meadow. No one bade me farewell.” A few years later, he transposed some of this song to a section of the First Symphony’s slow movement.

Play

Play

On many occasions in his earlier symphonies, Mahler brought whole passages from his songs into the epic worlds of his symphonies.

-

The central portion of the First Symphony’s slow movement is a restful passage of gentle simplicity that takes us far from the gloom of the funeral march.

-

Mahler is recalling the moment in the fourth Song of a Wayfarer, where the narrator forgets his troubles and falls asleep beside the road, under a linden tree. “On the road stands a linden tree. There I slept peacefully for the first time.”

Battle and Triumph

Play

Play

Play

Play

-

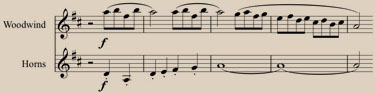

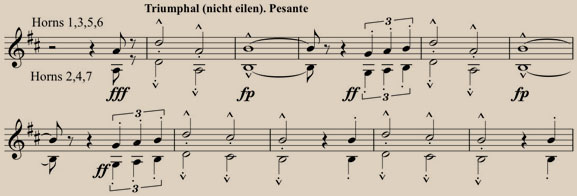

A different type of march appears after twenty minutes of struggle and turmoil at the symphony’s triumphant finish. This one manages to be both confidently swaggering and hymn-like at the same time. It grows louder and mightier with each repetition, as evidenced by Mahler’s note in the score: “From here to the end, it is recommended to reinforce the horns until the overwhelming hymn-like chorale has reached the necessary volume. All horn players should stand up, to create the greatest possible impact. If necessary, a trumpet and a horn can be added.”

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

Play

Play

Mahler made a daring harmonic leap back to the home key of D Major in the First Symphony’s Finale. He described the creative process that led to the breathtaking moment: Again and again, the music had fallen from brief glimpses of light into the darkest depths of despair. Now, an enduring, triumphal victory had to be won. As I discovered after considerable vain groping, this could be achieved by modulating from one key to the key a whole tone above (from C major to D major, the principal key of the movement). Now, this could have been managed very easily by using the intervening semitone and rising from C to C sharp, then to D. But everyone would have known that D would be the next step. My D chord, however, had to sound as though it had fallen from heaven, as though it had come from another world. Then I found my transition — the most unconventional and daring of modulations, which I hesitated to accept for a long time and to which I finally surrendered much against my will. And if there is anything great in the whole symphony, it is this very passage, which — I can safely say it — has yet to meet its match.

Humans in the Landscape

Play

Play

-

After opening the First Symphony with a vast landscape created by suggestions of natural sounds and a distant hunting call, Mahler calls for a faster tempo. The repeated cuckoo call turns into a sweet melody in the cellos, the movement’s first theme. The tune emerges naturally from its surroundings, as if a wanderer in the green hills were singing to himself.

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

The principal theme in the first movement of his First Symphony was first used by Mahler years before in one of his Songs of a Wayfarer. “I Walked Across the Fields This Morning” (Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld). One morning, striding across the dew-laden fields, the lovelorn narrator briefly escapes from his grief by opening himself to nature. The finch sings to him: “Isn’t it a beautiful world? Well, then?”

Play

Play

Evocations of the sounds of nature, realized through imaginative instrumentation, recur throughout Mahler's works. In "On My Love's Wedding Day" (Wenn mein Schatz Hockzeit macht), the first song of Mahler's Songs of a Wayfarer (Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen) the narrator finds himself in a countryside that has burst into bloom. High bells illustrate the Blümlein (little flowers) of the text, while solo flute and violin trill like a pair of lovebirds.

Creatures of the Landscape

Play

Play

“Even as a child I was struck by birdsong.”

Calls of various birds, real and invented, permeate Mahler’s musical world.

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

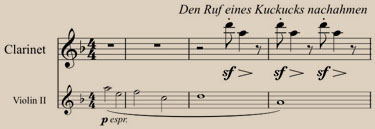

Why does Mahler change the call of the cuckoo?

-

Compare a call of the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus, 2011)

-

with its depiction in a harpischord piece (Daquin, 1720)

-

with the bird cadenza in the Pastoral Symphony (Beethoven, 1806)

-

with this folk song (Austria, before 1900)

-

and finally with Mahler’s repeated call in the First Symphony (1887)

Origins: Folk & Folkways

Play

Play

-

The second movement of Mahler’s First Symphony draws on the folk tradition of the Ländler, a heavy dance in 3/4 time. Here, its principal idea refers to the “Song of the Postilion.” In Mahler’s day, the post was delivered by horse-drawn coach, and the driver (or postilion) would play a horn or sing a song to announce his arrival.

Play

Play

This movement incorporates a variety of quick mood changes. At times, Mahler asks the horn player to change the instrument’s sound by blocking the bell with the hand. Mahler uses this “stopped horn” effect to produce a spirited, and vulgar noise, appropriate to a drinking song.

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

Mahler based the Scherzos of his First and most of his later symphonies on the Ländler, a rustic peasant waltz often accompanied by heavy stamping.

Origins: Synagogue

Play

Play

As a boy, the songs and chants Mahler would have heard in the synagogue may well have influenced his predilection to use certain melancholic melodic shapes and bitter-sweet tonalities.

Play

Play

Mahler's Methods

Play

Play

The turn had a long and deep significance for Mahler that dates back to his earliest musical memories. In the synagogue, he would have heard the turn frequently as a ornament in the chanting of the Torah: for instance, in the cantillation called gershayim. He would probably have even sung it while reading the portion assigned to him for his bar mitzvah.