Both Mahler’s First and Second Symphonies raise the question of whether Mahler intended his music to have particular extra-musical meanings. Throughout his life, Mahler struggled with whether and how to explain his music to the public. He originally named his First Symphony the Titan, and gave the movements the following titles:

—Spring without end

—A chapter of flowers

—With full sails

—Stranded! A funeral march in the manner of Callot

—From hell to heaven, as the sudden expression of a deeply wounded heart.

By the time of the music’s publication in 1898, he had withdrawn the second movement as well as these titles. Yet he returned to explanation in the Second Symphony, expounding his concept that the hero of the First Symphony is borne to his grave in the funeral music of the Second and that “the real, the climactic dénouement [of the First] comes only in the Second.”

-

Scary and spooky folk tales were an important thread in Mahler”s childhood experience. His first large-scale work, Song of Sorrow (Das Klagende Lied), is based on a story of a man who kills his brother, only to be confronted at his own wedding by the accusing voice of the dead man sounding from a flute made of bone: "A miracle, what now began, what strange and sorrowful singing! It sounds so sad and yet so beautiful. Whoever hears it wants to lose himself in sorrow! Oh sorrow, sorrow!"

-

Mahler originally intended to incorporate his setting of the Magic Horn (Wunderhorn) poem "Heavenly Life" (Das himmlische Leben) into his third symphony. However, the song finds a natural place at the end of the Fourth Symphony where its description of a child’s dream of what heaven must be like serves to heal all the previous movements’ conflicts. Throughout, the voice of the soprano soloist guides the listener like a beacon of light around which Mahler’s imaginative orchestral colors flicker joyfully: "Should a day of fasting come along, all the fish come swimming happily! There goes Saint Peer running with net and bait to the heavenly pond. Saint Martha will be the cook." His friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner recalled that in composing this movement "his mother's face, recalled from childhood, had hovered before his mind's eye; sad and yet laughing, as if through tears."

-

As the fourth movement of the Second Symphony, Mahler’s orchestration of the Magic Horn (Wunderhorn) song “Primal Light” (Urlicht) comes as a counterfoil to the comic tale of effort and frustration of the previous movement. Its spiritual certainty points the way to the transfiguration depicted in the finale’s last pages.

One of the many humorous songs in the Magic Horn (Wunderhorn) series is “St. Anthony’s Sermon to the Fish” (St. Antonius Fischpredigt).

-

It tells of Saint Anthony futilely preaching a sermon to the fishes: "St. Anthony arrives for his sermon and finds the church empty. He goes to the rivers to preach to the fish. They flick their tails, which glisten in the sunshine."

-

In the third movement of the Second Symphony Mahler expands this whimsical trifle into a whirling scherzo. It’s interesting to compare the resourcefulness of the instrumental effects, as well as the humorous way that the main theme seems to chase its own tail in a never-ending flow of sixteenth notes, with Mahler’s real-life efforts to build a career. He too often felt that he was “preaching” to unappreciative critics and audiences.

Play

Play

Play

Play

On many occasions in his earlier symphonies, Mahler brought whole passages from his songs into the epic worlds of his symphonies.

-

The central portion of the First Symphony’s slow movement is a restful passage of gentle simplicity that takes us far from the gloom of the funeral march.

-

Mahler is recalling the moment in the fourth Song of a Wayfarer, where the narrator forgets his troubles and falls asleep beside the road, under a linden tree. “On the road stands a linden tree. There I slept peacefully for the first time.”

Play

Play

The principal theme in the first movement of his First Symphony was first used by Mahler years before in one of his Songs of a Wayfarer. “I Walked Across the Fields This Morning” (Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld). One morning, striding across the dew-laden fields, the lovelorn narrator briefly escapes from his grief by opening himself to nature. The finch sings to him: “Isn’t it a beautiful world? Well, then?”

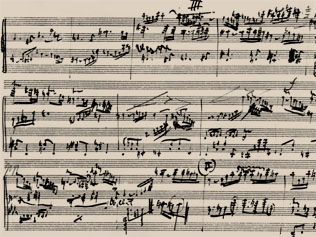

As the energy of the Rondo-Burlesque reaches its crazed climax, Mahler drops in snatches of famous marches of the Empire often used for celebrations and festivals:

-

He tosses whole phrases of Strauss’s iconic Radetzky March into his musical stew.

-

As director of the Vienna Opera, Mahler refused to stage a second-rate opera based on the life Hungarian patriot Rákóczy. So it’s only fitting that he also threw in fragments of the infamous Rákóczy March.

-

Screaming above the orchestral maelstrom, they seem to tease and taunt (In the score extract shown here, the Radetzky March is highlighted by orange notes, the Rákóczy by blue). Did the intrigue and spite that eventually played a part in Mahler leaving the Vienna Opera find an ironic reflection here?