Play

Play

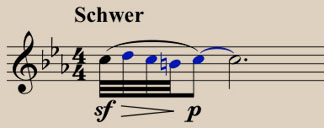

In Mahler’s later music, the turn, once a simple item of musical punctuation, comes to occupy a place of particular emotional significance. Here it is at the beginning of the last movement of The Song of the Earth (Der Abschied).

Play

Play

The turn had a long and deep significance for Mahler that dates back to his earliest musical memories. In the synagogue, he would have heard the turn frequently as a ornament in the chanting of the Torah: for instance, in the cantillation called gershayim. He would probably have even sung it while reading the portion assigned to him for his bar mitzvah.

-

The rocking motion of a lullaby, a cradle song, is the ironic background to a father’s remembering his daughter in "When Your Mother Comes Through the Door" (Wenn dein Mütterlein) from the Songs on the Deaths of Children (Kindertotenlieder): "When your mother comes through the door with the shimmering candle, it seems to me you always come in with her, scurrying behind just as before, into the room. Oh you, the too quickly, too quickly extinguished happy glow of your father's cell!"

The lyrical interlude of the Third’s Scherzo begins as if fragments of Tyrolean or Bohemian melodies are drifting up from the posthorn player’s unconscious. But soon Mahler mischievously lets the daydreaming solo meander into something strangely close to a popular Spanish tune of the time, the Jota aragonesa.

-

Many composers wrote fantasies on this melody in the nineteenth century. Here is an excerpt from the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt's Rhapsodie espagnole.

-

In Mahler's Scherzo, the violins smilingly answer with the Jota itself. By stretching out the tune, Mahler improbably turns it into a friendly vision. A modern American analogy would be adapting La Cucuracha for use as an inspirational hymn.

Play

Play

Mahler based the Scherzos of his First and most of his later symphonies on the Ländler, a rustic peasant waltz often accompanied by heavy stamping.

Each of the regiments stationed in Iglau had its own band, and each band came from a different corner of Europe. Nevertheless, military signals were the same all over the Empire, and literal quotes of these trumpet calls abound in Mahler.

-

In the Third Symphony, the call of “Fall in!”

-

brings the daydreaming posthorn back to earth.

-

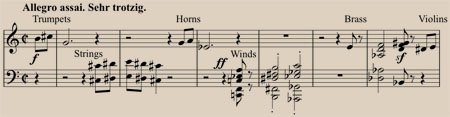

The Fifth Symphony opens famously and strikingly with a haunting trumpet solo that seems to warn us of approaching tragedy. The passage is made up of two common signals, changed from major to minor:

-

the General Appel (General Call)

-

and the call Habt Acht! (Take Care!)

Play

Play

-

In the Ninth Symphony's Rondo-Burleske, ideas appear and disappear like bubbles in boiling liquid. The music is as quirky in its sense of key as it is resourceful in part–writing, illustrating Mahler's maxim "Variety and contrast! That is, as it always was, the secret of effectiveness!" Is Mahler challenging his critics with music that is indeed “too clever by half"?

Mahler was devoted to the effortless lyricism and dramatic power of the music of his fellow Viennese Franz Schubert. Both composers were preoccupied with the way in which the tonality of a passage could hang between major and minor.

-

Listen to the opening of Schubert’s last string quartet.

-

Compare this passage, which acts like a motto for the pessimistic mood of the Sixth Symphony: underlined by a fate-like rhythm in the drums, the brief trumpet-colored glow of a major chord gives way to a plaintive minor chord of oboes.

-

Here it is again, near the very end of the symphony, underlining the tragically powerful descent of the strings' melody.